As a lifeline, waste depository and a catalyst for remarkable engineering feats, the Chicago River deserves to share its story. The founding of Chicago depends on this river. A Chicago bridgehouse turned museum now presents the river’s story. At the McCormick Bridgehouse and Chicago River Museum, visitors gain a new way of examining history through a natural lens while exploring magnificent feats of human engineering.

Presented in the Michigan Avenue Bridgehouse, the converted space is ideal for a museum sharing the natural and human history of the Chicago River. The Michigan Avenue Bridge (renamed the DuSable Bridge in 2010) first lifted in 1920. Its four bridgehouses featuring bas-relief sculptures were all completed by 1928. In 2006, the Friends of the Chicago River organization opened this museum to share the story of the river and its city.

Most of the visitor’s experience consists of trundling up close-quartered steep staircases and stopping at small landings. Each of these landings chronologically presents a portion of the river’s story.

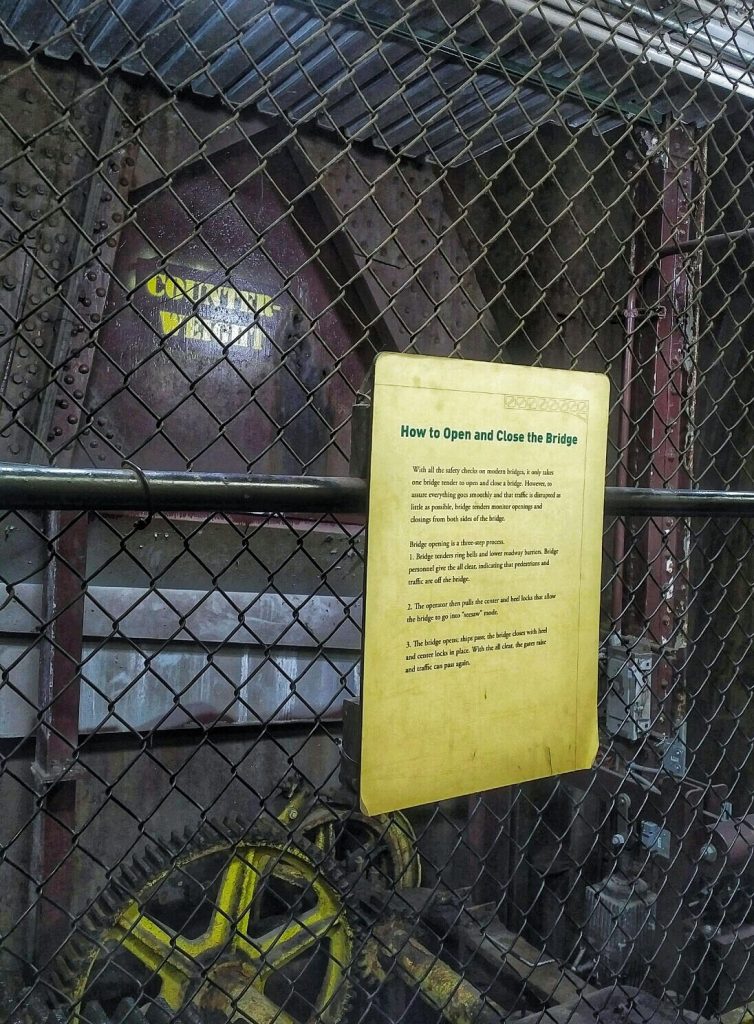

The experience begins at river level. You will want to start your tour by exploring the step-out area on the first floor. This gear room places you directly below one of the City of Chicago’s 37 movable bridges. Here, you can see the mechanics required to open and close a movable bridge (it can take up to 10 minutes for a bridge to open in Chicago, depending on the vessels passing). On special “lift days” at the museum, visitors can experience the full process. Watching a motor and seemingly simple gears lift hundreds of feet worth of metal into the sky, allowing boats to pass underneath, is sure to inspire a greater appreciation for engineering.

This is also a good place to learn about some of the most common types of bridges in Chicago and their distinguishing characteristics. Use this knowledge on your next walk in the city to see if you can identify different bridge types.

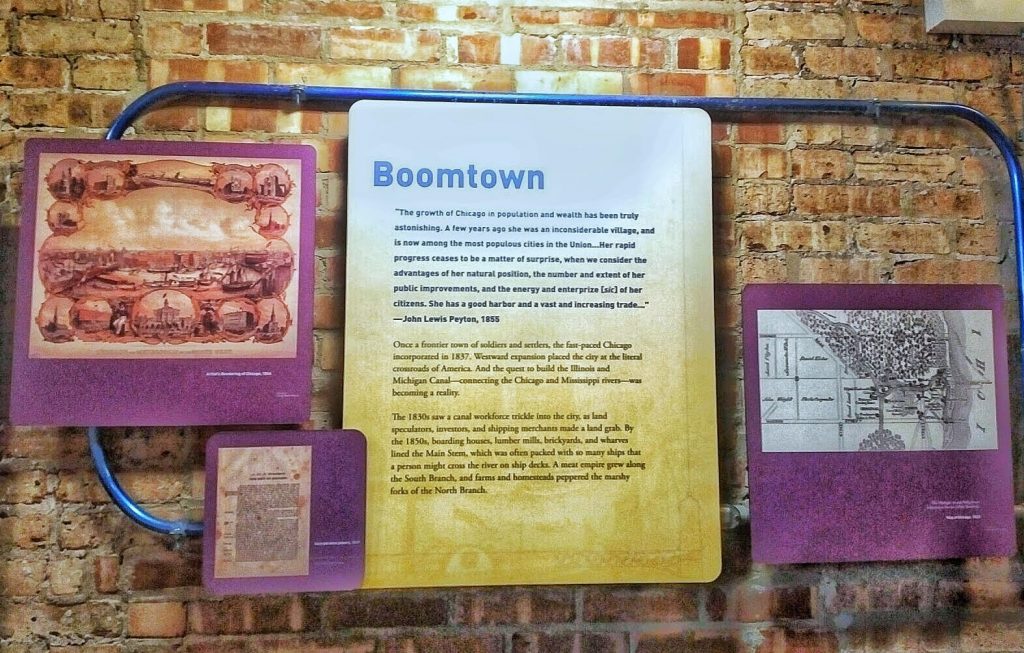

As you proceed upwards in the bridgehouse, you will learn about the natural history of the area and early settlement. At first, the area around the Chicago River was less than hospitable. However, the river’s pathway proved to be a vital resource for travel and trade for Native Americans including the Ottawa, Miami, Chippewa and Pottawatomi. The European fur trade brought more people into the area and a city was incorporated in 1837.

This swampy marshland and sparse trading posts became an urban center in a matter of a few years. The river became an important trade route and ships filled up the docks in Chicago. Industrial establishments formed along the riverbank including lumber, tanning and meat plants—with homes and small farms growing around them.

The legacy of this development and industry is seen at the museum. Large circular windows offer glimpses of the river, surrounding skyscrapers and the renovated river walk with its pathways, restaurants and bars. This is, in large part, what makes this museum interesting and effective. Although the museum displays few artifacts, it includes extensive information and sources about the changing landscape. Paired with interesting views, visitors gain a new perspective on urban development.

The Friends of the Chicago River devised the museum as a space to appreciate the river as both a natural and economic resource. The need for conservation is made clear as the museum shows how the rapid urbanization of the area in the 19th century had disastrous effects on the environment. Human and industrial waste were dumped into city streets, which shallow ditches diverted directly into the Chicago River. This fed into nearby Lake Michigan, the city’s source for drinking water.

Due to numerous citywide health problems, the flow of the river was reversed. The museum thoughtfully chronicles this impressive engineering feat with excerpts of newspaper articles, sketches and diagrams. Engineers ultimately reshaped the landscape, sending the Chicago River’s flow to the Mississippi River and eventually into the Gulf of Mexico.

The redirection of waste into other sources of fresh water caused tensions and, according to the museum this prompted the first pollution case to go before the Supreme Court in 1906.

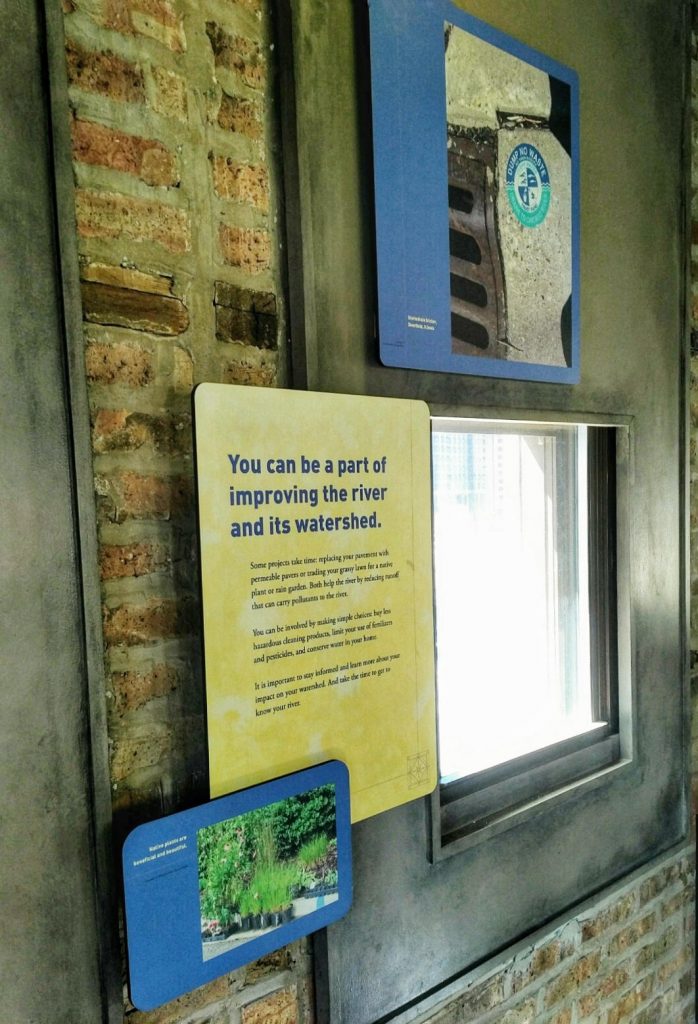

At the fifth and final floor, you are rewarded for climbing all the stairs with grand views of the city and river. This floor focuses on the diversity of the watershed. Colossal skyscrapers created with human technology line the river walk. The ongoing effort to restore the biodiversity of the area may also be visible with returning plants and animals as well as human spaces designed to integrate with the environment instead of dominating it.

This bright, open space is the perfect setting to learn about current conservation efforts and their effectiveness. The Friends of the Chicago River use environmental education to combat the toll of human activity on the natural habitat.

As one museum panel states, the past and ongoing causes of water pollution are not just major industry but “the combined impact of decisions made by everyday people.” After climbing several floors to learn about the degradation of the Chicago River, it is both figuratively and literally uplifting to place information on conservation efforts on the top floor.

The McCormick Bridgehouse and River Museum utilizes an alternative perspective (the river itself) to relay human history and its impact on the natural environment. The bridgehouse manages to provide an opportunity to connect with the river even while confined to a human-constructed space. The river’s story shows drastic actions are sometimes necessary to undo human damage to the environment. It also shows human ingenuity and conservation efforts can help restore what was lost.