Trapped inside a sinkhole, many mammoths and other Pleistocene animals died struggling to get out. Their lives were lost in the pit, but in a twist of irony, that very sinkhole ensured their remains would last for millennia. After 26,000 years, the bones were discovered and the resulting dig site turned into a museum.

Nestled among the Black Hills of South Dakota, in the small town of Hot Springs, paleontologists are hard at work uncovering an enormous depository of Pleistocene flora and fauna. Although mammoth bones are displayed at many museums worldwide, this site offers a unique experience. The Mammoth Site is an active dig site that allows you to embark on a journey to appease your inner archaeologist.

A guide takes small groups on a walking tour around the site—stopping to explain the findings and methodology along the way.

Mammoths

The tour begins inside the visitor center and gift shop where a replica mammoth stands tall above the crowds. A sign above the entrance to the enclosed dig site reminds us all that, “There will never be more mammoths. They are extinct. If we do not take care of their remains today, they will not be here tomorrow.” This plea for conservation reverberates throughout the tour experience.

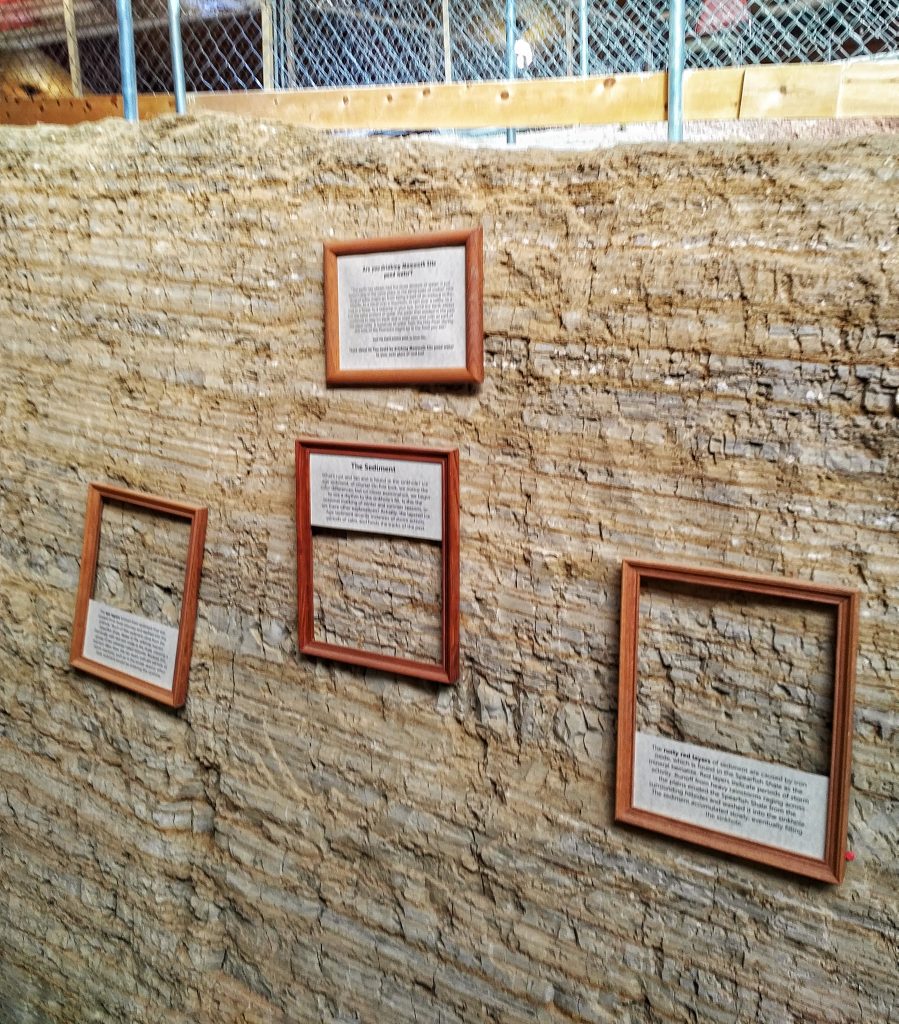

Guides provide listening devices and lead you into the enclosed dig site. As you enter, you will immediately notice partially uncovered mammoth remains emerging out of a sinkhole. The oval sinkhole—hundreds of feet across—formed as water seeped through red shale in the area, dissolving the underlying limestone and creating a cavern that eventually collapsed. This sinkhole filled with sediment and contained a thermal pool of artesian spring water. The warm water likely created an environment suitable for vegetation, attracting unsuspecting mammoths that slid down the slick walls of the sinkhole.

The tour revolves around the circular paved pathway surrounding the dig. The pavement and guard rails starkly contrast against the sand pit and the partially uncovered bones flecked across the terrain.

Discovery

The site was discovered in 1974 during a construction project. After digging up what were eventually identified as mammoth tusks and bones, the land owner permitted an excavation project. By 1975, the site became a 501(c)(3) and an active area for researching and promoting education of paleo environments. Since then, paleontologists and volunteers have been working to uncover the remains. Now, the Mammoth Site and Museum has the largest collection of mammoth bones in the world.

As a guide leads you around the pathway, they explain the work being done and what has been discovered so far. In addition to Columbian and woolly mammoths, at least 87 other species of Pleistocene animals have been found. Short-faced bears, camelops, coyotes and wolves are just a few of the other animals whose remains were discovered. It is possible that some of these carnivores descended into the sinkhole to feast on the dead mammoths and were trapped as well. Bones of smaller animals including ferrets, moles, frogs and snails were also uncovered.

Excavations are typically conducted at the site in two 2-week sessions during the summer with two additional groups of Rhodes scholars working there in 1-week intervals during the fall and spring. This allows the paleontologists to catalog and map findings in the fall. Since the area is enclosed, there is no need to cover the site and remains—which is what makes this place so remarkable for visitors. It is possible to visit while active work is going on, but it is also available year-round to see the remains in situ. It is a snapshot of a work in progress.

Paleontologists at Work

The tour guide points out and explains the different layers of strata. The individual layers created by the sediment reveal the age of what is discovered there. The further down you dig, the older the findings will be. The guide and placards mounted along the pit’s interior explain the different formations of the sediment. If you look closely, you can see pockets of gypsum that formed throughout the walls.

Brushes, trowels and markers periodically dot the landscape. At the site, you have an in-depth look at the plaster casting process. Plaster casting is important because it helps preserve the layout of a found specimen before it is removed from the site for further study. The plaster is laid over, hardens and creates a mold that can be used for research. While walking around the site, you will notice some of this work in progress and see the casts over bones.

The tour’s contiguous path offers multiple perspectives on different areas of the site. The surrounding walls also contain informational panels on mammoths and other Pleistocene animals. If you are able to pull your attention away from the emerging finds of the dig site, you can explore the theories concerning mammoth extinction and how paleontologists are learning more about these animals through the study of their bones and teeth.

A visit to the Mammoth Site allows an exploration of a significant location for paleontological research and an insight into process.

Learn More in the Gallery

After the guided tour, visit the exhibition gallery adjacent to the dig site. It features excavated bones and full casts of some of the uncovered animals. This is a great opportunity to appreciate the size and scale of many of these animals. After all, on average Columbian mammoths weighed eight tons and stood twelve feet tall at the shoulder.

Did you know that the length of a mammoth’s tusk can help determine the animal’s age? This is true of all mammoth relatives, including modern-day elephants. The thickness of the tusk’s dentin can also reveal information regarding the climate when the animal lived.

The gallery also features an interactive map where you can trace the areas where mammoths once roamed. It is remarkable that such a large and wide-roaming animal no longer walks this planet. Although mammoths and many other Pleistocene megafauna have long since died out, exploring this museum reminds you to appreciate what is here today and what may not be around tomorrow.