2018 was a year imbued with significance in Prague. It was 100 years ago, following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, that the new democratic country of Czechoslovakia was founded. One of the highlights of the centenary celebrations was the partial reopening of the National Museum’s main building. Cloaked under scaffolding, the building had been languishing at the top of Wenceslas Square for the last seven years.

It seems entirely fitting that the unveiling of this handsome building should be at the heart of commemorating the last 100 years of Czech and Slovak history. Not only has it been the backdrop to some of the nation’s most abhorrent scenes – Nazi troops parading in the square in 1939 and the Soviet-led invasion of 1968 – but the mass demonstrations of the 1989 Velvet Revolution also took place in front of its steps. These peaceful protests began the return to democratic rule.

It is in part a testament to the museum’s iconic status that, since its reopening on the 28 October 2018, a throng of local and foreign visitors can be found queuing around the block each morning to gain access to its renovated interiors and exhibitions halls. It is a trend that has persisted into winter, despite the dropping temperatures. No doubt, the large lines have also been the result of the museum waving its entry fee until the end of the year, coupled with the building’s current maximum capacity of 300 people due to the ongoing works.

The plan was for the entire museum to open to the public in time for the October celebrations. But, as with many ambitious national building projects, politics and legal wrangles pulled the schedule off kilter. Despite the museum closing in 2011, work didn’t begin until 2015. This resulted in only two temporary exhibitions spaces being open for the grand reopening.

Over the next two years, the permanent exhibitions spaces should also be completed, alongside a children’s playroom, an interactive center for students, and a café. 2019 will include the addition of a multimedia walkway - linking the historical building to the New Building of the National Museum next door. And as a final flourish, visitors will be able to ascend into the Museum’s dome in order to take in panoramic city views. The hope is to transform this 200-year-old institution into a modern, inclusive space.

So, grand plans are afoot. But what for now? Does its partially opened interior suggest that a state-of-the-art museum is to come?

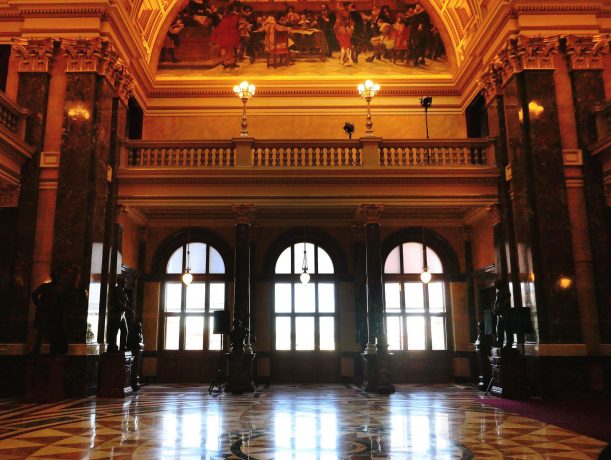

Certainly, the restored museum entryway has an impressive impact. The grand stairways clad in maroon carpets and lit by ornate golden lamps - which lead into a magnificent high-ceilinged atrium - are as swoon-worthy as the Neo-Renaissance exterior would imply. Equally, visitors who climb to the first floor for a peek at the yet-to-be-reopened Pantheon will be wowed by its beauty and scale. But there are also discreet modern elements – such as screens showing time-lapse and animation films about the building’s history and reconstruction, which demonstrate this is no longer a museum frozen in the 19th century.

The new temporary Czech-Slovak / Slovak-Czech exhibition, which runs until June 30, 2019, also seeks to breathe new life into both its own and some borrowed collections through contemporary curation. Over two thousand important documents and cultural artifacts are placed alongside multimedia recordings and touchscreen panels. The aim is to tell the story of the last 100 years of these nations’ joint history. As well as touching on their stories since the 1992 break-up and the formation of two separate nation states.

The result is an interesting and multifaceted sense of perspective, capturing both a broad political view alongside more personal accounts. Visitors can glimpse significant documents, such as the Pittsburgh Agreement, the Munich Agreement and the Hácha-Hitler Declaration, while a large video screen shows footage of key people and places in the nation’s history. Ondrej Nepela’s Olympic medal is displayed with footage of the winning performance. Touchscreen quizzes help visitors understand the changing cost of living. Whereas phone booths around the exhibition hall tell the stories of ordinary people’s experiences of life in the new state.

And so, the first large-scale exhibition at the National Museum for seven years hints at good things to come. With a magnificent building, 200-year-old history and a wealth of collections, the reopening, despite the delays, probably would always have been a success. But in trying to enliven its space and move away from the dusty, reserved atmosphere of its former self, the museum looks to be positioning itself as somewhere that school children and students, as well as older generations and tourists, will flock to visit. And that, after all, will be what makes it a museum of the nation.