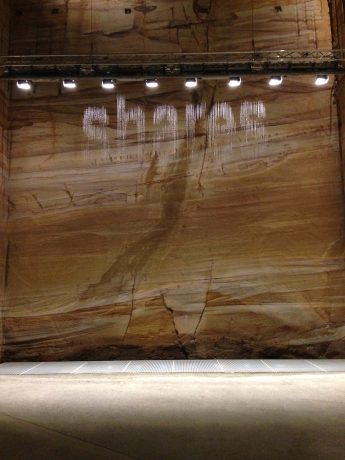

Descending the spiral case, it is easy to feel you are underground. On one side, the rough concrete wall turns to sandstone and a glass elevator shaft drops below. Voices above become muffled, and, as you descend deeper, natural light gives way to luminous yellow. Then you are in The Void, an expansive corridor where the roof towers overhead. Sounds drone and whirl. The sandstone wall continues long and high and, if you look closely, you can see the circular marks where the saw cut deep into the earth.

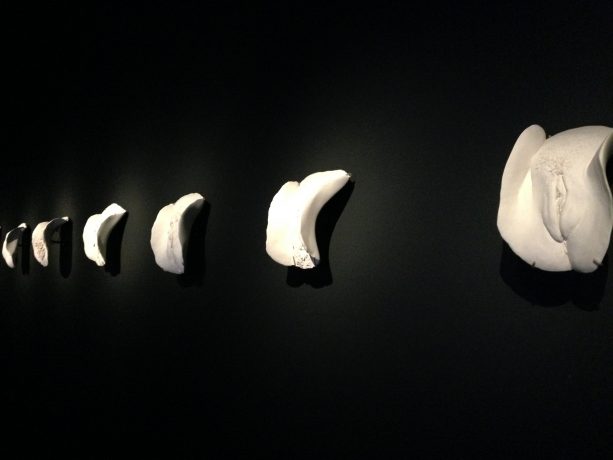

But you are not underground, and this is Mona’s first deception. Mona’s purpose is to deceive. The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) is a privately owned museum located in Hobart, Australia. It is controversial in both its collection and ethos, focusing broadly on the themes sex, death and what it means to be human. Mona’s ambition, according to its website, ‘is to understand how narrow, how partial, our view is of the world. To see clearly, we argue, you have to first know the limits of your vision.’

Fender Katsalidis is an esteemed architecture firm based in Melbourne. Their brief for Mona was simple: functionality before design. In this building, owner David Walsh wanted a space that was free from constraints – both physical and otherwise. The result is a gallery that is solid and heavy, but fluid and moving.

‘We didn’t want to create a neutral space for the art,’ says James Pearce, Director of Architecture at Fender Katsalidis, ‘but an active, living one—a space the art responds to. ‘

Deception really begins on approach. Mona is situated on a peninsula outside of Hobart, a 20 minute drive along the Brooker Highway, or a 30 minute ferry down the River Derwent. From the car park, the museum is tucked behind a music stage and a restaurant – a misleading wander over a green hill and down a garden path. From the jetty, a 99 step staircase (think Aztec temple) leads up, up and up, building anticipation. But the entry itself is not monumental. To the right is a trampoline (a work by artist Chen Zen) and in front, a tennis court (all white lines and red squares). But there is a door, plated in mirror; and as you move closer, the reflections draw you in.

Pearce describes the mirrored doorway as an ‘event horizon’ – a term in astrophysics denoting the point of no return. It gives a sense of entering another world. This world is, at first, the original home of the Alcorso Family, Italian migrants who bought the peninsula in the 1950s, establishing Tasmania’s first vineyard on the site. Roy Grounds, noted Australian architect, designed the building in 1957 and its original aesthetic is preserved; an enormous, freestanding fire place sits beside the café, and a paved sandstone floor leads toward the museum’s information desk. It is from here that a spiral staircase leads down into the depths.

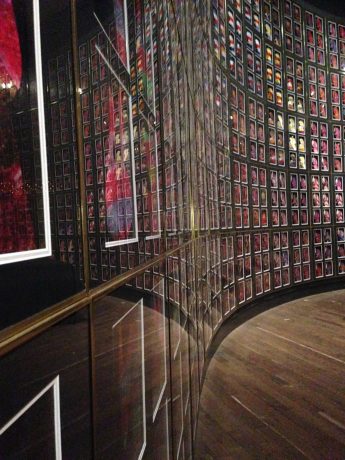

Once inside Mona, there is no guiding path to follow. Visitors ascend from floor to floor via a rusted steel staircase and artworks are suspended in the space: Bit.Fall by Julius Popp, the day’s most-googled-words in water, falling from the roof above; Cloaca, Wim Delvoye’s poo machine, hidden in a corner of the gallery spaces, emitting a strong stench of stomach gasses; and Tim, the tattooed man, who sits meditating, looming across The Void below. It is in this way that, as Pearce notes, the art and building are combined.

Deception continues throughout the visit. Rounding a corner on the lower ground level there is a tunnel, dark and eerie, leading to the Round House, the second home designed by Roy Grounds on the Mona site (1958). The floor here is carpeted, the walls wooden and the space quiet. This is where Mona’s library is, an expansive collection of books on everything from art to science. They are not lendable but they are readable, and arm chairs stand in the corners of the room.

Rounding the corner from the library the darkness lessens, and the corridor narrows. And suddenly you emerge out into the light. In front is Sternenfall, an artwork by Anselm Kiefer. It is made from glass and sheeted lead stacked on three high shelves; as the lead softens over time the glass sheets fall, shattering on the floor below. On either side are windows onto the outside world. Green grass rolls from the building toward the River Derwent, where a cathedral, designed by artist Wim Delvoye, stands on the water’s edge.

The underground allusion is broken and, standing in this space, it easy to question Mona’s very purpose: playground or art gallery? It walks both lines and, like the building that houses it, is purposefully confusing. But here beside the Kiefer work it is possible to, just for a moment, see Mona from the outside – to see David Walsh’s intensity and eccentricity; his excitement and love. Before turning around and entering his deceptive world once more.