There are places so powerful that you need to get hold of yourself and just be there in that moment of silence after your visit. One of the most energetically dominant museums with the quietest exit is Yad Vashem – Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust.

Established in 1953 (new building dedicated in 2005) the museum is located on the Mount of Remembrance, overlooking Jerusalem. We visited the memorial and got a chance to talk to Moshe Safdie – renowned architect, theorist and author, who created one of the most grandiose and simultaneously touching museum buildings of the world.

“There have been more meetings per square meter on this project than any other project I ever undertook” Moshe Safdie, Yad Vashem Architect.

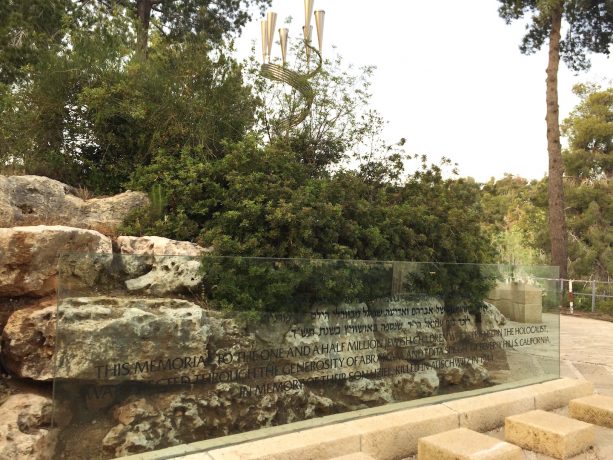

Yad Vashem complex consists of the Holocaust History Museum, Children's Memorial, Hall of Remembrance, The Museum of Holocaust Art, Valley of the Communities, a synagogue, a research institute with archives, library, publishing house, and The International Institute for Holocaust Studies. It is much more than a museum with 800 000 visitors annually, international research workshops, events, seminars, lectures, and most importantly some 190 million pages of Holocaust-era documentation, 465 000 photographs, 171 000 items, artifacts and artworks.

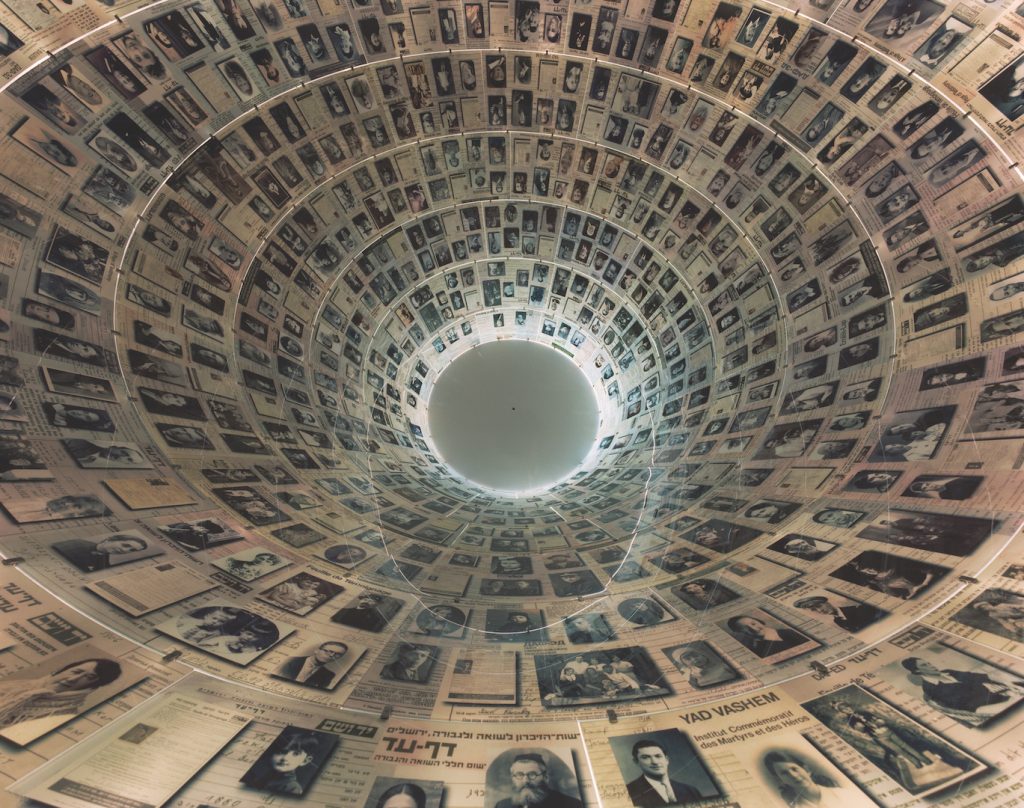

One of the most impressive testimonies of the Holocaust sweeping horror is presented to the public in the Museum. When you enter The Hall of Names you cannot believe your eyes: circular repository, housing some 4.6 million names with empty spaces for those yet to be submitted. The hall so emotionally powerful it is hard to hold back tears. But tears are in the eyes of every visitor – all halls tell the story of horror, fear, catastrophe.

The Holocaust History Museum is shaped like a triangular concrete prism that cuts through the landscape. So you basically walk in the mountain, following a preset route that takes you through underground galleries. While you get more information, see more evidence, touch objects and look into the eyes of martyrs you inevitably indulge in philosophizing, and right when you think there is no light at the end of the tunnel, you come outside of the mountain to see the heavenly view of Jerusalem, feeling that all those souls are somewhere here above the Promised Land.

We were stunned by the silence of the place even though it was crowded, but no one was making selfies, everyone rather felt like contacting parents, kids and loved ones. We immediately wanted to ask the architect, Moshe Safdie, how did he come up with the striking idea of a museum in the mountain.

The building cuts through the mountain, it can be interpreted as an arrow, as a scar. What was the symbolism behind the project?I have referred to the reception building as a sukkah. It has a trellis-like roof, bringing in soft, striped light, which evokes the quality of light in a sukkah. It is the preparatory space that leads you from day to day city life to the sacred space. They bridge between the reception building (mevoah, in Hebrew) and the historic museum prism-like structure is across the bridge, emphasizing this transition. I do not think I was thinking of any specific symbolism in proposing the structure that penetrates the mountain. The idea emerged first from the desire not to have a large building on top of the pastoral hill of Yad Vashem. The program is extensive and as the other proposals indicated, would have resulted in a large, very omnipresent building on top of the hill.

That led to the idea that you could penetrate the mountain and accommodate all the gallery spaces underground, not affecting the pastoral quality and allowing the visitation to extend across the mount. Of course, I was thinking that, by penetrating the mountain from the South, there is a kind of violent act and the museum structure descends at 5% slope to give the sense of deeper and deeper penetration before reversing and climbing up towards the light. From the outset, I had in mind that the conclusion of the journey would be coming out of the mountain towards the North, to light and to life. This sequence of penetrating the hill and coming out to light was first explored in the Children’s Memorial, which I designed 15 years before designing the historic museum. It is given here, even more powerful expression.

The theme is so difficult to tackle, how long was the project in the works?The process was very complex: It took three phases of an international competition before they became convinced that the concept of penetrating the mountain is feasible and desirable and thereafter endless meetings with the steering committee and the advisors. I like to say that there have been more meetings per square meter on this project than any other project I ever undertook. It took 10 years from the competition to the completion of the historic museum. The old historic museum remained open as we constructed this one. Access to it was by temporary bridge, which flew above the excavation and later removed.

There was no direct, organized consultation with survivors; a number of members of the steering committee, however, were survivors. The main thrust in coordination of these efforts was under the direction of Avner Shalev, who acted both as director and chief curator of the museum. There has been much response from survivors after completion – all very positive.

Yad Vashem is living up to its motto: “Remembering the past. Shaping the future”. It is one of those museums that keeps history alive and doesn’t let us forget what Nazis wanted us to never know. Exactly 72 years ago, July 22 1944 Soviet forces were the first to approach a major Nazi camp – Majdanek near Lublin, Poland. Surprised by the rapid Soviet advance, the Germans attempted to hide the evidence of mass murder, but in the hasty evacuation the gas chambers were left standing to present the horrinle evidence. In the summer of 1944, the Soviets also overran the sites of the Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka killing centers.