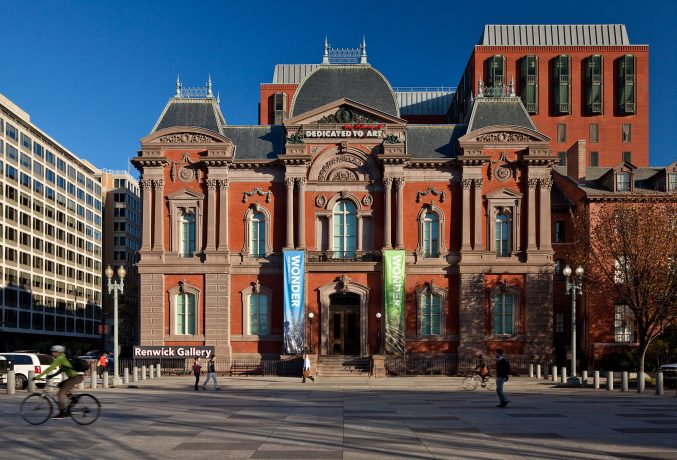

Buzzing with activity, hoards of selfie stick clutching tourists, interspersed secret service officers, a couple of police cars, and a Trump impersonator populate the main stretch of Pennsylvania Avenue outside the White House. While across the street, a much smaller, but still substantial crowd lines up outside a striking red-brick building. Built in 1858, the Renwick Gallery now holds the Smithsonian American Art Museum's program of contemporary craft and decorative arts, a cultural gem celebrating creativity and innovation amidst one of the most politically charged and symbolic sites in the world.

Originally commissioned by William Wilson Corcoran, a prominent 19th century D.C citizen, to house his collection of American art, and once dubbed the “American Louvre,” the Renwick Gallery was always intended to be a public museum. Corcoran aimed to cement America’s status as a model nation not only through industry, trade and military prowess, but also cultural development. Designed by James Renwick Jr. (known for designing St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City) and inspired by what were at that time new architectural additions to the Louvre in Paris, the building initiated the popularity and influence of French modern architecture, also known as Second Empire architecture (a style developed under Napoleon III’s reign). Indicative of this are the pavilions, mansard roofs and double columns, still preserved today.

Following a massive two year renovation, the Renwick re—opened in 2015 with a new lighting system featuring LED lights, significantly improving energy efficiency and decreasing the building’s environmental footprint. Additional new highlights include a red carpet designed for the grand stair by architect Odile Decq. Suspended above which is Leo Villareal’s glittering installation Volume, consisting of white LEDs, mirror-finished stainless steel, custom software, and electrical hardware, giving visitors a celebrity worthy welcome, and reinforcing the museum’s dedication to showcasing modern crafts, decorative arts and architectural design.

No better exhibition encapsulates this aspiration more so than No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man,” currently on view. The week long annual Burning Man event is a cultural movement manifesting itself in a temporary city, for which large scale experimental art installations are created. Emphasizing the importance of community, self-expression, creative freedom, and appreciation for all things hand-made, not commodified, the essence of the festival is similar to the Renwick’s. The scale of works in particular denotes the scope of cooperation imperative to their execution, as well as the innovation required to overcome technical challenges.

The exhibition consumes the building, the enormity of each installation often overtaking the entire expanse of a room, overwhelming viewers through size, grandeur, and sheer intricacy of craft, inducing a sense of theatricality, compelling them to interact with the piece. To begin with, viewers enter an immense paper arch created by Michael Garlington and Natalia Bertotti, covered in a collage aesthetic with wild and gothic motifs. Proceeding forward one can see Marco Cochrane’s towering luminous sculpture of a woman, Truth is Beauty, asking the question, “What would the world be like if women were truly safe?” Among other eye-catching works on the ground floor are Duane Flatmo’s mystical Tin Pan Dragon vehicle, Five Ton Crane Arts Collective’s immersive recreation of a movie hall, and Richard Wilk’s Evotrope - a whimsical glistening spinning wheel and unicycle hybrid reminiscent of a flying contraption from Around the World in 80 Days.

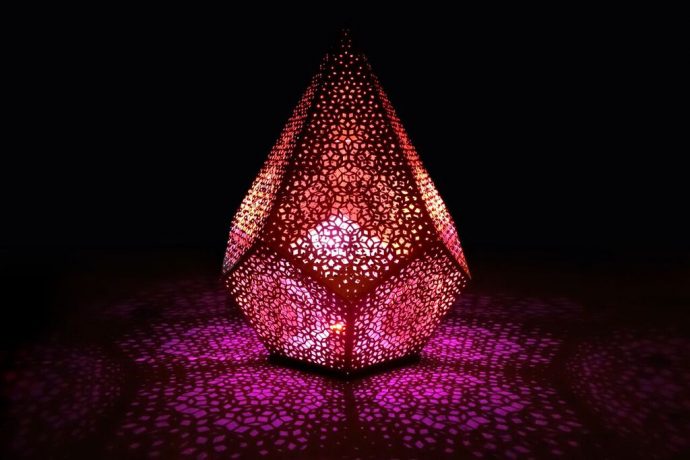

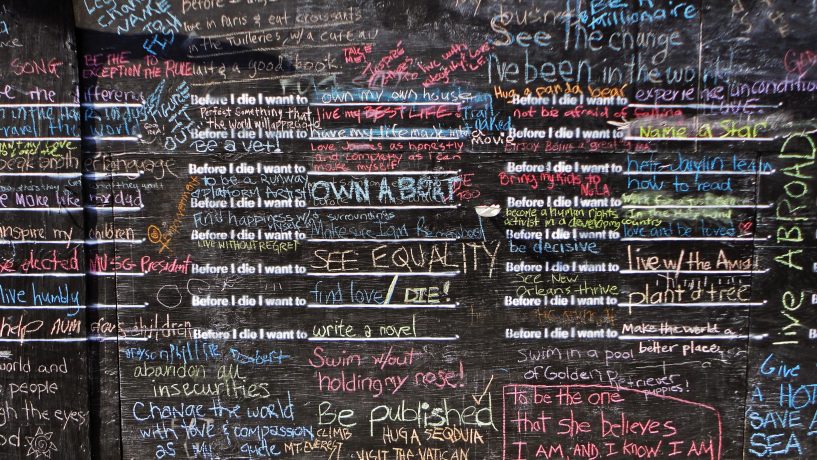

Many more spectacular creations await visitors on the second level of the gallery. The largest and most awe-inspiring work greets viewers as they reach the top of the staircase, David Best’s Temple (especially commissioned for this show). Rendering a large hall in to an actual temple, Best doesn’t create an artwork but an atmosphere. Walls befitted with intricate wood carvings, the ceilings tiered with sharp gold structures, Best creates a moving space that could inspire skeptics to reflect. Aiding in the enhancement of this meditative state are Aaron Taylor Kuffner’s golden gongs in his Gamelatron Camerlang installation. Christopher Schardt’s Nova and FoldHaus Art Collective’s Shrumen Lumen provide an immersive meditative experience more psychedelic in nature. Schardt’s digital star suspended over a room full of viewers watching changing colors particularly elicits a milder, calming reaction, while the large neon hued mechanically controlled mushrooms in Shrumen Lumen amuse and entertain with irregular bursts of movement. More plays with color, and it’s interaction with light and shadow is visible in HYBYCOZO’s breathtaking installation Deep Thought.

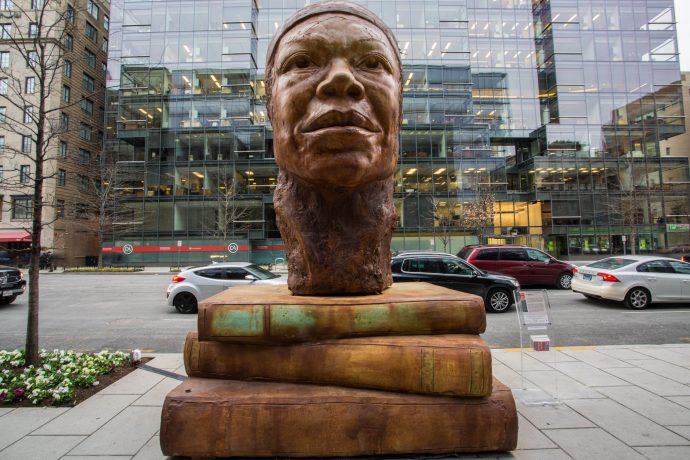

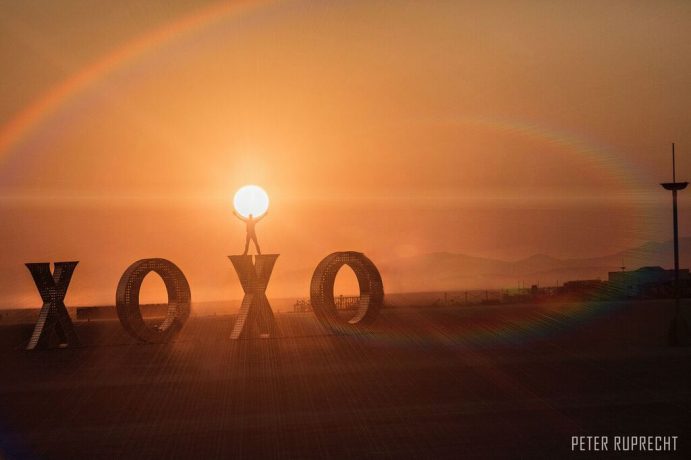

Each space in this 19th century structure is completely transformed by the free spirited contemporary aesthetic associated with Burning Man. The exhibition however, is not just relegated to the interiors of the gallery, but spills outdoors, adorning D.C’s central business district. In collaboration with the Golden Triangle Business Improvement District, the Renwick attempts to bring art into the daily lives of the public. Six installations including Laura Kimpton’s metallic XOXO sign, Ursa Major’s unmissable large bear, Kate Raudenbush’s intricately carved doorway, Jack Champion’s oversized sculpture of a crow, Mischell Riley’s powerful Mayas Mind, and HYBYCOZO’s elaborate Golden Triangle, contribute simultaneously to DC’s public art program and Renwick’s original intended mission in transforming D.C’s status from being more than just a government and political center, to a cultural hub.

With the words “Dedicated to Art” inscribed in stone above the front entrance, the Renwick makes their mission remarkably clear, by putting on view immersive exhibitions that provide a new perspective on contemporary art through a focus on bringing American decorative arts and crafts to the forefront and affirming their significance in this digital age. Their location, set among powerful political institutions, further intensifies the resonance of their showcased artworks often alluding to concepts of equality and unity, cementing their status from a cultural accessory to a cultural necessity.