San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park is surrounded on three sides by busy streets and a packed city, with the fourth facing the chaotic northern Pacific Ocean. And yet none of this seems possible when you’re standing in the middle of the park, surrounded by redwood trees disturbed only by the occasional tendril of fog or gust of wind. Naturally, this park is home to one of San Francisco’s premier arts institutions, the de Young Museum.

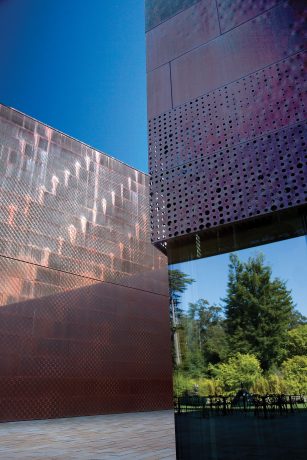

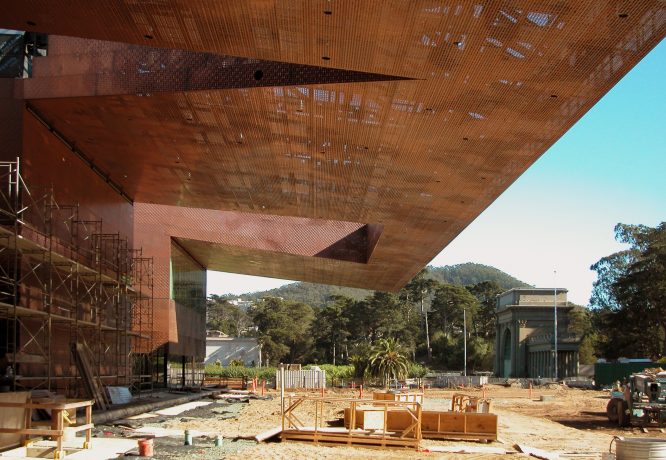

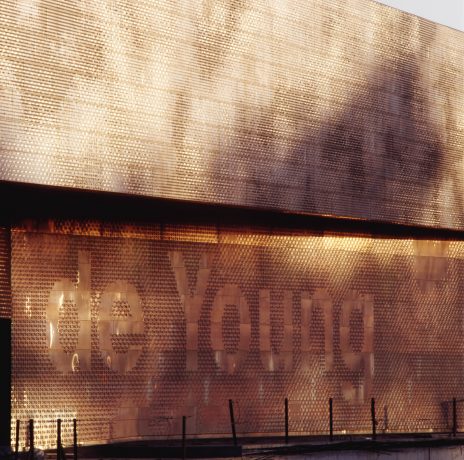

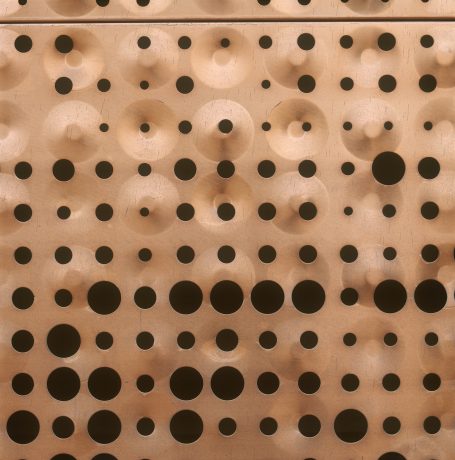

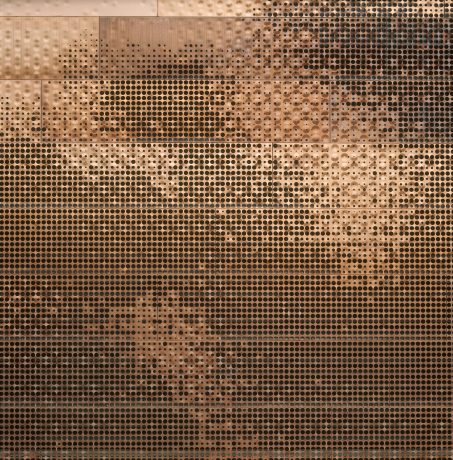

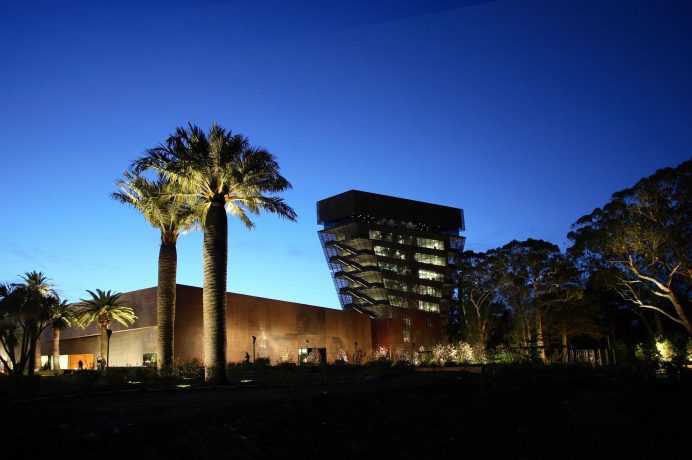

It’s been a staple of the park since 1895, but underwent quite the makeover in 2005. The previous building was completely demolished and replaced by the iconic copper facade designed by Pierre de Meuron, Jacques Herzog (of Herzog & de Meuron, naturally) and Fong + Chan. It’s more than just an aesthetic wonder; due to the very active fault lines beneath San Francisco, the de Young had to be capable of weathering earthquakes. The building can move up to three feet without being structurally compromised.

The architects also made a significant effort to make the building approachable - literally. There are entrances to the main hall on all four sides, so visitors can access it from north, south, east, or west. The structure itself is posed similarly. Herzog & de Meuron and Fong + Chan intentionally chose natural materials to construct the museum with, like wood, glass, stone, and copper, allowing it to meld with the surrounding park.

The building's most iconic feature is its nine-story tall Hamon Tower, a strange triangular structure that defies comparison. It's sort of like an inverted pyramid, or maybe more like a wall lamp? The top-heavy nature of the building almost appears to defy the laws of physics. In any case, the view from the apex is unbelievable with the surrounding hills studded in jewelry-box houses, while downtown glitters in the distance.

This is always the first place that we visit, even before we check out the galleries or grab a cup of coffee from the de Young Cafe. There’s something incredible about this view, especially after exploring the city for years. If you don’t have the time or money (the trip up to the observation deck is free) for anything else at the museum, then this is the place to go. Not only does the tower overlook the city, but the rest of the building is visible from the top as well. From above, it’s a series of undulating copper blocks, split by straight lines and seemingly random skylights opening up to the galleries.

Anyone familiar with chemistry, coinage, or the Statue of Liberty knows that copper tends to oxidize over time, turning from a rich brown into a ghostly green. The de Young’s architects were well aware of this when they coated the outside of the building with almost a million pounds of the metal, as it’s supposed to subtly change colors over time. We find this a particularly interesting choice, given the general nature of museums and how their job is often to prevent such changes from occurring. Few curators would be keen on the slow oxidation of their precious metal collections, or the ripping of priceless canvasses; however, the de Young seems, in this case, to embrace the decay by acknowledging that sometimes the accrual of wear can be part of a compelling story. In any case, we can’t wait to take someone here in several years’ time and claim that we remember the building when it was brown.

Take the elevator (or the stairs, if you’re particularly daring) back down to the concourse level and you’ll find yourself in the airy entry court. It’s fun to walk around after seeing the layout of the museum from above, like getting a life-size, 3D version of the ubiquitous museum map.

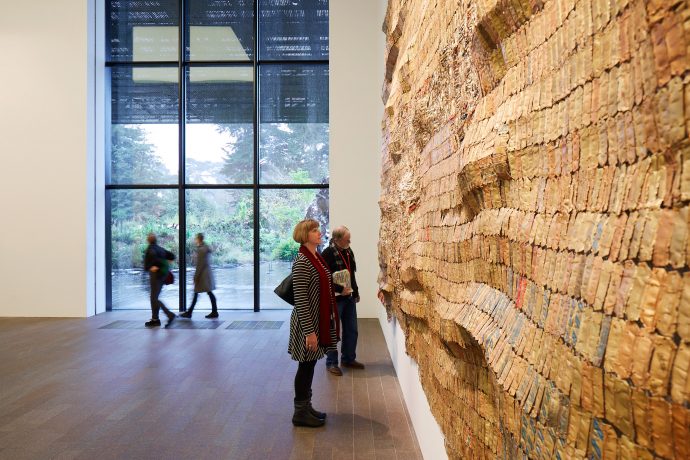

The galleries themselves are rather massive and house some of the most unique and diverse art to be found in San Francisco. What stands out is the fact that it’s all so different, both from other objects within the collections and what can be seen elsewhere. There are a handful of very specific things you won’t see there - namely historic European art, because that collection is so massive that it’s housed in the Legion of Honor, a few miles north at Land’s End Park. There also isn’t much in the way of Asian art, because the Asian Art Museum, located in downtown San Francisco, thoroughly covers that subject. But pretty much everything else is fair game. There are 13th-century wooden sculptures from Africa, colonial American oil paintings, and contemporary sculptures from Oceania.

Permanent galleries are arranged in an interesting manner, one rather unique to museums I’ve visited before. Some of the art is grouped by location, for example there’s a pretty massive space on the upper gallery level dedicated to objects from New Guinea. There’s also another on the concourse level (the naming of floors in San Francisco is never as easy as “ground level,” since the hills make two or three levels actually on the same plane as the ground. The de Young apparently has forgone all of that and come up with their own system) with only Native American objects. This is par for the course, as many museums employ such a method to arrange their exhibits.

One of my favorite things to do is to track the European influence on American art prior to the twentieth century. Sculptures and paintings are pretty much indistinguishable from the collections at the Legion of Honor, but there’s also a temporal element in the curation. Multinational art from the twentieth century onward is separated from the rest, a tribute to the increasingly globalized nature of art. Additionally, costumes and textile are sequestered in order to be appreciated as a whole as opposed to intermixed with the rest. The holdings are still manifold: couture worthy of any international fashion week, hippie outfits from 1960’s San Francisco, and textiles from just about everywhere imaginable.

While wandering in between several thousand years of human artistic activity, you might notice some of the hidden gardens. They’re tiny green spaces, tucked into the middle of the museum at various points, and serve as a reminder that not all beauty is created by human hands. There are two full of ferns, which makes it feel like you’re looking through the glass into the Jurassic. Speaking of which, we like to finish up my visit with a trip to the bigger gardens around the museum. It’s not hard to see why San Francisco is such a popular place to live; this small section of Golden Gate Park is a compelling enough argument for the virtues of making this city home. Everything here is well-landscaped, and there are always pockets of wildness hidden by small groves of trees; these are quite clearly what the nooks of green in the museum are based on, albeit here on a much larger scale.

If your feet are too tired for further exploration (which is entirely understandable, given the nearly seventy-five thousand square feet of exhibition space), there’s always the cafe terrace, where anyone can enjoy an espresso and look out on the Barbro Osher Sculpture Garden. The de Young, to me, is always truly original. There’s not simply “something for everyone,” but rather something for everyone to discover, learn about or fall in love with.